Like many people, I’ve signed the contract for 2026. Unlike some, I’ve been thinking. There’s the bluster about Iran, the invasion of Venezuela, the bullying of Greenland. Sudan, Gaza, and Ukraine have fallen off newspapers’ front pages and people’s memory. That Fucking Woman unconscionably being shot in the head. This has been an explosive beginning of the year.

Worldwide misery apart, I live a local sadness: the anniversary of the Mother of All Almond Trees who isn’t anymore. That almond tree, the one who signified hope, renewal, nourishment, and resistance in Arabic and Mediterranean cultures. She had reached a full unkempt, hippie-hair canopy spreading this way and that with total disregard to symmetry. Despite neglect, she grew to her top height, her slender trunk bending this way and that, scared by seasons and bugs. Still, hers was the first sign of life by mid-January, pink whispers of spring amid the rosemary and lavender blues of winter. Her boughs yielded to a chilly breeze or a January storm, and showered the area with pale pink confetti, an early carnival that lasted about two weeks. Every year. Every mid-January, since I first arrived in the Algarve.

The almond tree grew on a bend of the road, behind a house. It added colour, movement, and life to a corner that met a brick wall to one side, and a short, weedy hedge to the other. She was the star of that corner. One day, I was driving by when I noticed the surprise removal of the hedge. The almond tree had already been dismembered into twigs and logs. The hedge had turned into a metal fence overlapped with a tight green plastic mesh to maintain privacy. Of course: after this wrongdoing, the neighbour needed to hide behind the fence. His name is written with spilled sap on the vast emptiness left by the almond tree. Now being mid-January, when almond flowers unfold, each time I pass the house on the bend with its sterile fence I feel that my soul has lost some of its seasonal sustenance.

So, I’d like to think I’m still in the cooling off period of my 2026 contract, and there must be a get out clause somewhere in the small print. I wish to cancel the current contract and get another year with another provider.

There are several worldwide calendars that do not claim 2026 as their year. Fortunately or unfortunately some are related to religion, others to political or monarchical events, or to the seasons, which I’d prefer. I’d also prefer a calendar that does not start on January 1st, and shuns the strictures of the Gregorian calendar, under which I’ve lived most of my life. It’s time to try something different. I might even try several calendars in tandem and throw parties according to the seasons.

I’ve looked at the usual culprits: Chinese, Hebrew, Islamic, and Hindu calendars among others, but I’m interested in stuff that doesn’t advertise itself or demand the obligatory bottle of bubbly, and doesn’t get rammed down your throat every day. Also, I dislike those sentimental calendars with pictures of kittens frolicking around a knitting basket, or beaches I’d never wish to visit. I want a calendar without days and dates and years if that were at all possible.

Below are some of the calendars (if that’s what they are) I’ve investigated.

Andean Winter Solstice

I’d like to celebrate Inti Raymi, the Inca Festival of the Sun, in the heights of the Andes, on 21 July. If possible, at Machu Pichu, in Peru. But Cusco would do. Andean peoples, among them the Quechua, don’t celebrate a new year, but they do celebrate the winter solstice in the southern hemisphere, and as the Sun faces its rebirth, so does everything else in nature.

Plants are considered people for the Andean folks, who treat nature as part of the community. Their sacred tree is the quinine tree (Cinchona officinalis), considered the Tree of Life, which is a plus in my book. Chinchona bestowed blessings on many lives worldwide, as it yielded quinine to counteract malaria. I can adapt: not all trees need to be almond trees.

According to chronicles by Garcilaso de la Vega, Inti Raymi was first enacted in 1412, then it was forbidden by the Spanish conquistador and the Catholic Church in 1535. The rebirth of the festival occurred in 1944, based on Vega’s accounts. Today, actors represent the original peoples of the Andes, and tourists trample Cusco for celebrations. Special foods reign, possibly prepared with some of their 4,000 varieties of potatoes, as do processions, masks, music, and a general good time. The Sun rules the universe (regardless of what some tin-pot dictators may think), and we all depend on it. The Andean calendar has no year number to it, which is liberating, as I’d never get old. You just exist, bathed in solar blessings and nature’s gifts.

Balinese Calendar

Bali has been favoured by the gods for its geography, temples, and calendars. It’s no small feat to deal with three calendars that have very little, if anything, in common, and still discharge one’s spiritual and temporal responsibilities in an orderly, serene, and magical manner. Or, at least, that’s what tourists think.

The first Balinese calendar is called Saka, derived from the Hindu calendar. It consists of 12 months, each with 30 days. Each month begins after a new moon, so it has 15 days of waxing and 15 days of waning. The Saka sports 24 ceremonial days, and the most important date is Nyepi, the New Year, also called Day of Silence. The next Nyepi occurs on March 19, 2026 (yes, that’s the Gregorian calendar raising its head). During Nyepi, Bali shuts down, nobody works, cooks, uses mechanical gizmos, and everything slips into tropical hibernation for a day.

The second Balinese calendar is called Pawokon, and it follows the rice harvest tradition, and determines market days. There are no years in the Pawokon calendar, just days and weeks. It offers 210 days distributed in 10 weeks. Week one has one day, week two has two days, week three has three days, and so on, until week ten, with its ten days. Every day, from each week, has a different name, making up 55 days whose names the population has to memorise and work out its position in the calendar. It doesn’t help much that the ten weeks roll concurrently, or not, and one day could have ten different names. Whatever god responsible for inventing this calendar must be laughing his head off, because it’s been confusing the Balinese people to this day. Maybe that was the intention, to keep people on their toes.

Festivals are calculated according to either calendar. Knowledgeable mystics calculate the most auspicious days (or not) for planting, harvesting, pruning, or for a wedding, blessing of a house, cremation, or that traditional coming-of-age ceremony, teeth filing. After girls have their first menstruation and boys change their voices, they have a communal teeth-filing ceremony that is supposed to help them reach Nirvana or something like that.

On top of these two local calendars, the Balinese people have been saddled with the Gregorian calendar for their official businesses. Which is a pity, because it’d be ideal to just forget what’s happening in real time in the outside world and worship the sacred banyan tree, dedicate one’s whole year to celebrate nature, introspection, spiritual enlightenment, community harmony, puppet shows, sacred dances, offerings, and some teeth filing. And eating the traditional babi guling, a whole-pig extravaganza, drinking Arak, a spirit made from coconut palm sap or glutinous rice served from bamboo containers, the whole a defiant feast in the largest Moslem country in the world.

Byzantine Calendar

Byzantium (which became Constantinople, nowadays Istanbul) named an empire, an era, a calendar, and everything that was produced then in terms of art, sciences, and excessive bureaucracy. The Byzantine Empire (originally named Eastern Roman Empire), lasted from 330 to 1453, and its main language was Greek. The eponymous calendar showed the year starting on September 1, and through the centuries it has determined days and holidays to the Eastern Orthodox Church, Russia, and the satellite countries of the empire. Today, it’s used in the Republic of Georgia, where its inhabitants also observe the Julian and Gregorian calendars, just to be on the safe side of all the saints, while they have a good time with three times as many festivities and holidays.

The Byzantine calendar followed early Jewish and Christian traditions and established the date of creation as September 1, 5509 BC. Now, in 2026, the Byzantine calendar has reached the respectable year of 7534. It seems a good calendar to skip all the confusion that seems to be spinning our way in the next centuries.

Trees were important for the Byzantines, and their significance has reached us today. The tall cypress signified immortality, and that’s the reason they adorn cemeteries. The olive tree meant peace and wisdom, both of which we need today by the truckload.

Holocene Calendar

Cesare Emiliano, a famous Italian scientist who had his fingers in many pizzas, thought the Gregorian calendar was full of holes and we needed a new one. He justified his new calendar with several arguments that included, but were not restricted to, the fact that the Gregorian calendar had no year zero; and that the most important date of Jesus’ birth, year one, was, according to scientists, more likely to have happened on year four. (I have no idea how he calculated this, but I’m comfortable with my lack of knowledge on this topic).

So in 1993 Emiliano proposed the Holocene Calendar based on the Holocene Era, or our more recent geological epoch. This, according to Emiliano, would add 10,000 years to the current Gregorian calendar. Today, if we were using the Holocene Calendar, we’d be stumbling on year 12,026 and feeling the weight of millennia on our shoulders and joints.

I dislike the lack of idealism in this calendar. Emiliano didn’t mention trees, or if there’d be any in his year 12,026.

Inuit Calendar

The Inuit people are distributed widely and have survived in some of the coldest places on the planet: Canada, Alaska, and Greenland. Wherever they are though, they celebrate the end of winter during the Festival of Quviasukvik. On December 24, they watch the sunrise, and until January 7, families and communities meet around a fire to share tales and food like whale, seal, and cakes. They believe that through sharing, they will survive in inhospitable places. That reminds me that the Inuit have just celebrated the end of darkness, and immediately after Greenland was threatened with an unhinged Trumpian invasion. I hope the Inuit don’t share anything with you-know-who.

The Inuit calendar differs from others due to geography. In the extreme north of the planet, they have six months of night, and six months of light. Well, in theory. There are only two seasons, winter and summer, but customs change according to the community location. Some Inuit communities live deep in the Arctic Circle, and they don’t see any sun up between December 12 and 29. A friend who did research in the Canadian Arctic told me of his elation when he noticed the first blades of grass, or something akin to grass, popping up from the melted snow. It was his sign of spring. It would be too much to expect an almond tree to grow in the Arctic region, so I’d have to be content with a blade of grass.

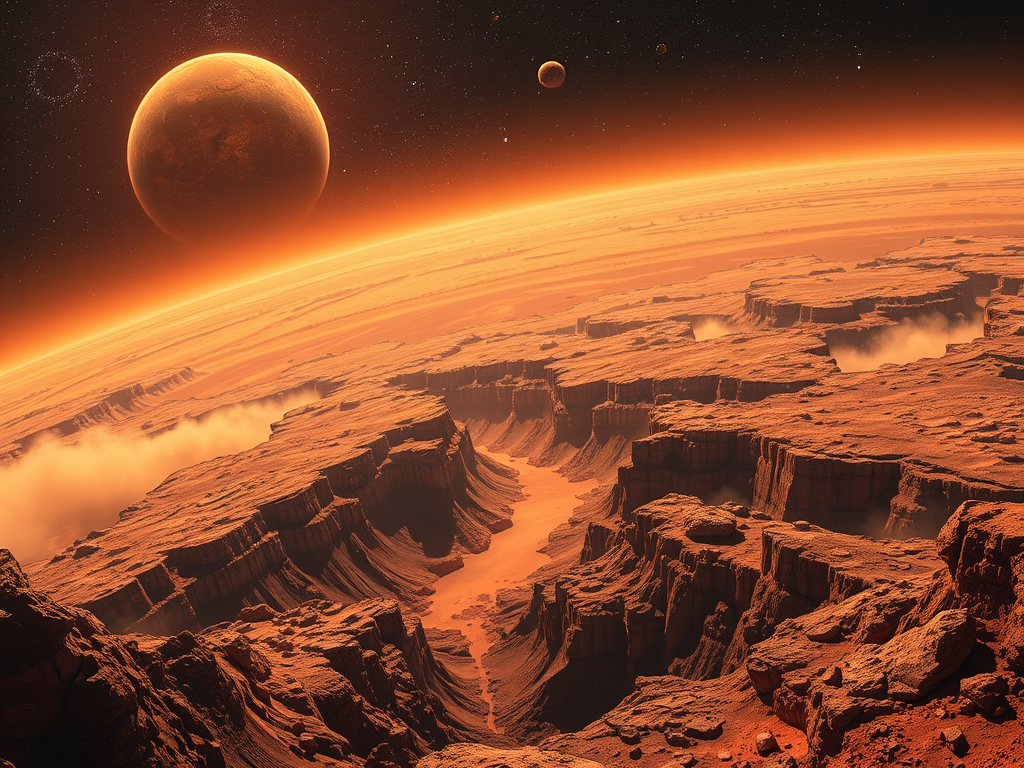

Martian Calendar

I’m sure it’s been a good year on Mars, with its equivalent of 687 Earth days. As far as I know, they haven’t got dictators that have survived on that dry and cold planet. But the local calendar has been invented by earthlings. Year 1 of the calendar was arbitrarily chosen to be the year 1956, when scientists observed a planet-wide dust storm. A flood on Earth, a dust storm on Mars. Each to his own.

Would almond and olive trees grow on Mars? I fret for the almond tree, but there’s a saying here that an olive tree never dies – it always comes back to life, regardless of the environment. And I bet they don’t have yearly contracts over there.

Music of the Rant: Holst, The Planets, “Mars”. BBC Proms, YouTube

P.S. 21/Jan/2026 – I’ve edited two “s” out of this blog entry because they were in the wrong place. One had been added to a verb, when it should have been resting elsewhere; another was a noun that belonged to an idiomatic expression, so it had no right to be essed around. I doubt you’d notice any of them, but there you are. Be well.

One response to “What year is this?”

How educational!

Get BlueMail for Android

LikeLiked by 1 person