Before Carter discovered King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, and mummies took Manhattan in 2017, mummy-mania had attacked many a society. Before we screamed and hid behind the sofa when mummies scared us with their curses in literature and films, mummies were used for surprisingly beneficial and happy endings. Well, most of the times.

Since the 1st century, Mummia, that is, powdered human and animal mummies, has been a medicine for kings and the population at large: it protected one’s general health, and worked well against epilepsy, coughs, and headache. Mummia was great to clean your teeth, stop blood loss, ease bruises, and aid menstruation. Of course, Mummia cured the plague, too, and I suspect it was the first medication for heartbreak and ingrown toenails.

Catharine de Medici and François I of France were great fans of Mummia. Royal doctors treated King Charles II of England with medication coming from human skulls, or Caput mortuum as it was called then. For a European King to eat parts of a pharaoh’s mummy was a splendid thing, because king and pharaoh were both on the same power level. Royal cannibalism made total sense.

To supply Mummia to a Europe of delicate health, mummy dealers desecrated a huge number of tombs in Egypt. However, with a finite number of mummies around, and the ever-increasing need for the medication, mummy dealers started to sell fake mummies as the genuine article. Apothecaries were able to distinguish the differences between a real and a fake mummy, especially those who went through a type of instant mummification. But the deal breaker arose when people got wind that fake mummies were made from the bodies of executed prisoners and slaves, or when commoners were killed to be mummified. By then, forget that gorging on mummy powder was the healthy option for a royal in feeble health.

Not everyone praised Mummia. In 1582 Ambroise Paré wrote in his Discours de la mumie that “this malevolent drug” does “nothing whatsoever to improve patients, (…) it also causes them terrible stomach pains, foul smell in the mouth, and great vomiting.” Ew.

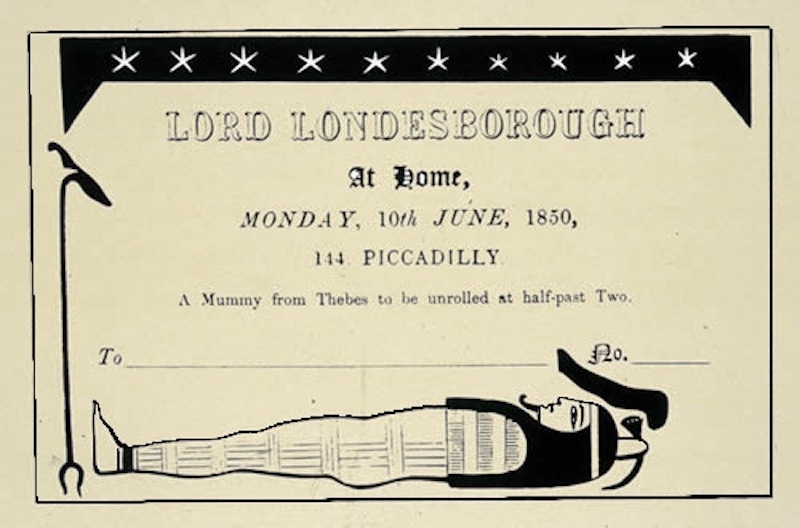

But all was not lost in mummy world. The Victorians saved the mummy’s skin, as to say, by having spirited mummy (fake or otherwise) unwrapping parties. Those were the most sought-after society parties in which mummies were unwrapped in front of august guests. The spectacles happened in hospitals, theatres, homes, and learned institutions, and a learned scientist (of sorts) was always in attendance. It is said that the parties were smothered in gin and ended in the early hours, with much merriment. Back then, people didn’t need to wait for Halloween to have a good time with a mummy, as disrespectful as that was.

In 1888 an Egyptian farmer discovered a tunnel containing a huge number of cat mummies, and he sold most of them as fertilizer. Many countries adopted the practice of using animal mummies as field fertilizer, including the UK.

Since Mummia was sold by apothecaries, and so were artists’ pigments, it took a jiffy before someone used mummy powder mixed with oils to paint a panel or canvas. Mummy brown was in vogue until the 20th century. Ground mummy produced a translucent brown pigment valued for flesh tones and shadings in paintings. Some artists debated which part of the mummy was best: dried flesh, or muscles, with or without bones or fat. Benjamin West, in 1797, once president of the Royal Academy, recommended “mummy, the most fleshy are the best parts”, for translucent glazes. Eugène Delacroix used it while painting the ceiling and side walls of the Salon de la Paix at Paris’ City Hall. The Salon was inaugurated in 1854, but it burned down in 1871 (Was it a curse?), and few sketches remain. Across the channel, The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1850’s to 1900’s) aspired to paint as if they were living before the time of Raphael (1483-1520), the great renaissance painter, and used mummy brown without knowledge of its real contents. When one of the Brotherhood’s exponents, Edward Burne-Jones, found out during a Sunday lunch that his mummy brown had real human remains in them, he dropped what might have been his Yorkshire pud with gravy, and dashed off to give his tube of paint a proper burial in his garden. Burne-Jones never used that colour again.

Richard Sugg, meanwhile, points out that “For a long time, charges of cannibalism were used as an effective slur against tribal peoples in the Americas and Australasia.” Yet for centuries, Europeans had no qualms about consuming human remains for health — particularly if those remains came from ancient tombs in the Middle East.

Mummies have gradually found the respect they deserve and made their way into properly refrigerated and temperature-controlled conservation chambers in museums. Or to proper burials. The oldest mummy in the world, about 8,000 years old, was found in Portugal’s Vale do Sado. Although I have been unable to locate the mummy, I hope no artist pulverised it and used it in a contemporary painting or sculpture, trying to convince us of their high art, or scare us. Mummies seem to have disappeared from circulation, but they still play tricks in our imagination.

You must be logged in to post a comment.