One day in 1847, when Pedro II was 22 years old and apparently bored with his Oh, so tedious life as an emperor, he decided to play a type of Monopoly with the vast lands he had inherited from his father. Well, no, the lands were not inherited directly.

His father, Pedro I, had abandoned Brazil and Pedro II to fight his brother-cum-son-in-law in Portugal. Before that, he amassed all the money he could by borrowing against his properties in Brazil. Did Pedro I repay his debts? Of course not.

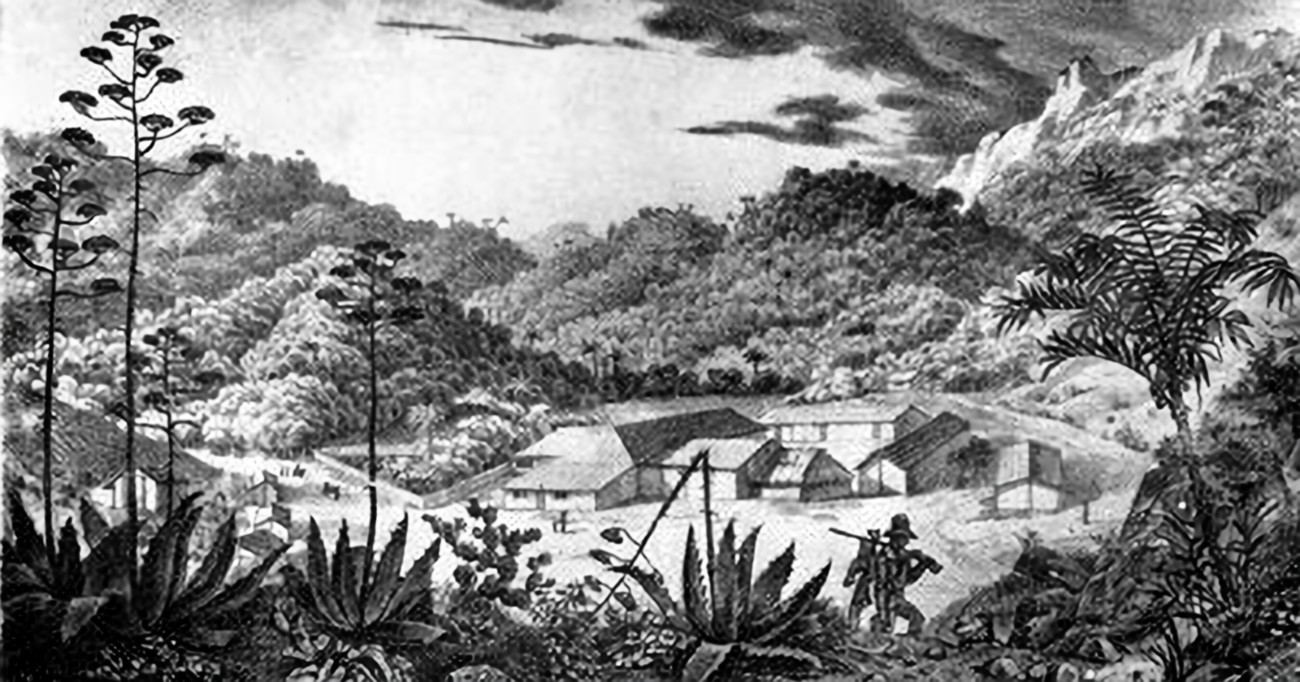

Pedro I’s creditors decided to sue, and his properties were auctioned. But a nice guy, the Marquis of Paraná, decided that the Concórdia Farm, formerly known as Córrego Seco Farm, located amid the serene hills beyond Rio de Janeiro, would be better kept as a government property. They shook the creditor’s hand on the amount of 14 contos de réis, today’s €65,500.00. Donald Trump would have approved the deal.

When Parliament declared Pedro II’s majority at age 14, Concórdia Farm was formally given to the new emperor as a present from the country. (Trump can only dream…) This is the land Pedro II decided to play Monopoly with, but first the name Concórdia wasn’t very imperial, so he renamed it Imperial Farm.

Pedro voiced his desires of partitioning the Imperial Farm, and after a while accepted the proposal made by his “Counsellor, Chief-Official, and Butler-in-Chief of the Imperial House,” a Paulo Barbosa da Silva. Pedro ordered the plan written in his Butler-in-Chief’s Book, describing parcels of land, and donating land for the church (St. Pedro de Alcântara), and the cemetery. There was also the small detail of a brand new imperial summer palace. And the fact that the German immigrants populating the new town had already been there for a while. But that was a minute thing for an imperial butler to solve. Besides, Petrópolis was soon populated by Swiss, Portuguese, French, Italian and English immigrants.

I repeat, those grandiose ideas were written out on a Butler-in-Chief’s Book. Pedro II signed them in the foundation decree of Petrópolis. It seems like a private deal: Parliament did not approve the deal into law.

The chunks of land were rented out to the settlers for nine consecutive years at a time. Settlers were allowed to build houses, shops, or whatever they wanted in the land, that is, add value to the original property. If a settler wanted to sell the house and if they wanted to pass the land on, the new occupier would have to pay a laudemium, or the prince’s tax, of 2.5% on top of the rent. For perpetuity.

I think Pedro II, a man curious about scientific developments, would have been puzzled by Einstein, who said that time is a construct. The emperor would have undoubtedly asked, “How long is perpetuity?” I don’t know what Einstein would have said. But I believe he mentioned something to do with time that flies. Like pigs. Oh, stop me, I’m being erudite again.

At first, the rent and the prince’s tax went to the Superintendência da Imperial Fazenda (SIF – Imperial Farm Superintendence), which was, in fact the Imperial House. After the Proclamation of the Republic in 1889, SIF reincarnated as Companhia Imobiliária de Petrópolis (CIP) and it now operates from Princesa Isabel’s Palace in Petrópolis.

These days, the prince’s tax works very much the same way, and the tax is the same whether the property is in a rich or poor part of town. The new owner pays the 2.5% directly to CIP, and this tax does not go through the government. Only after obtaining his CIP receipt is a new owner allowed to get his deeds for the building, but never the land. Very feudal.

CIP is a private limited company whose shares are not negotiated in the stock market, and belong to a few people (usually a family). CIP is not inspected or regulated by the Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission, but it files its federal tax papers. Its president and three directors all display the imperial surnames de Bourbon de Orléans e Bragança, except one of them who bears the more ordinary, and shorter, Orléans e Bragança. Poor guy.

In reality, nobody among us commoners knows the exact size of the original Córrego Seco, or the Concórdia, or the Imperial Farm. One reference to the deeds of the land quotes its size as one league in the front by almost half a league deep, which corresponds to about 2,150 hectares in Petrópolis. As Pedro’s hunger for land increased, the imperial farm portfolio grew: Quitandinha, Itamarati, Morro Queimado. What else has been annexed or sold, and what has become part of CIP/Imperial House territory? We do not know. Secrets seem concealed in a well-guarded, palatial subterranean vault: how much was inherited, by whom; how much is the current value of the legacy; what is the amount CIP collects; how much do CIP’s shareholders receive each year.

In 2008 CIP administrator Paulo Tostes declared that the laudemium received was reinvested in the Mata Atlântica around Petrópolis, and some historical buildings in town. The leftover money was divided among the family. The whole family sings from the same hymn sheet (they are very, very Catholic). Do you believe that story? Me neither.

People in Petrópolis are not keen to pay the prince’s tax in the 21st century. In 2020, a federal member of Congress proposed a law to end the prince’s tax. The decision was voted down because the Constitution of 1988 protects acquired rights. In 2022, two members of Congress proposed the use of the prince’s tax to prevent environmental disasters in the Petrópolis area. There are over 200 lawsuits from Petropolitans who query the calculation of the prince’s tax, or don’t want to pay for the privilege of supporting a spectral imperial family that lost its lofty place over 130 years ago.

However, one could possibly detect an imperial hand behind some events. The family was allowed to return to the country in 1945, but as commoners, no titles attached. The unelected president João Figueiredo, during the dictatorship, issued a presidential decree turning Petrópolis into the Imperial City. And for some extraneous reason, Fernando Collor, Brazil’s youngest president elected after the dictatorship (1990-92), himself invested with the honour of being impeached for corruption on his second presidential year, signed on the dotted line to allow the imperial family the use of their titles again.

Please don’t think there are no cracks within the born-again imperial family. Also, do not believe in the fallacy that only commoners sue other commoners. In 2018, four (or ten according to different accounts) perpetually-hopeful uncrowned heads from the Brazilian imperial family dashed to a proper court with lawyers and judge (Gasp!) flapping their minority 28.5% CIP shares and complaining about their low or inexistent returns. Unhappy with an administration that, apparently, overpaid itself, presented incomplete shareholders’ meeting reports, and operated a company that had filed results in the red for many years, the Gasping Gang of 28.5% forgot imperial etiquette, blood ties, and demanded the proper valuation of all CIP’s properties. They wanted the majority shareholders to buy their minority gasping shares at current value. How vulgar.

Nobody knows exactly how the imperial legal samba party ended. Apparently, the lawsuit was settled (?) and it has suddenly become a private, family business again, everyone singing from the same soporific hymn sheet, etc. Which probably means that a lot of money must have rolled among gasps of “More! More!”

Now, one of those who went to court was Duarte Pio de Bragança, Duque of Bragança, the pretender to the inexistent throne of Portugal, whose family was banished from Portugal in 1910. He is Pedro II’s great-grandson, and also benefited, perhaps not as much as he would have wished, from the prince’s tax paid in Brazil. This came up recently in Brazil because Duarte’s daughter got married and some thought Petropolitans were subsidizing the wedding party for 1,200 people at Mafra National Palace, while the Portuguese taxpayer paid nothing. Which sounds true. In an interview in 2006, Duarte said that when his family was exiled in Switzerland (nice gig if you can get it), his mother received an income from Brazil, and each time a property was sold in Petrópolis, they were paid 1%. In 2020, Duarte said in an interview, “The whole area where Petrópolis is built belongs to my mother’s family [descendants of Princess Isabel], and from there we receive an income.” This sounds like a royal “Put a sock in it” moment, but Duarte royally paid no attention.

Perhaps we must rejoice at Duarte’s partial transparency. For it seems that even though the imperial or royal families were both exiled without any money, theirs or taxpayers’, somehow they managed to receive their portions of the Petropolitan prince’s tax. What I’d like to know is how come Pedro II, the man who invented the tax itself, had to live his last years on handouts from friends. And who has, really, been receiving the money?

When rainstorms devastated parts of Petrópolis with landslides, floods, and countless deaths in 2022, the laudemium raised its head again after another imperial put a sock in it moment. The pretender to the inexistent Brazilian throne, one Bertrand de Orleans e Bragança, who titles himself imperial prince of Brazil, sent a message to the inhabitants of Petrópolis stating that “the imperial family (…) is always ready to serve its people, and offers our prayers and solidarity.” After many distressing and derisive comments, the grand imperial prince mentioned that the grand imperial family was busy collecting donations for the people of Petrópolis. Yeah, right. Thanks.

When Bertrand was asked about returning some of the laudemium money to the suffering inhabitants of Petrópolis, he said that he did not receive any money from the laudemium, because his father had sold his shares of the company in the 1940’s. Besides, he was from the Vassouras branch of the family.

Ah, yes. The Vassouras branch. The Petrópolis branch. One receives the prince’s tax, the other doesn’t. There’s bad imperial blood in there somewhere, something to do with giving up all imperial rights for perpetuity. (That word again.) I think I shall write about the two branches before perpetuity ends.

Meanwhile, pass go and do not collect €100. Mind those people getting out of jail free. I bet they know who to blame: Gasp! The butler did it!

You must be logged in to post a comment.